China is big. China is powerful. And now, China may be the best place in the world to file a patent lawsuit, says Erick Robinson of Beijing East IP

We all know that patent rights in the US have been systematically destroyed over the past decade. Beginning with eBay, and ending with the hypocritically named America Invents Act, patent cases have become harder to file, longer and more expensive to adjudicate, more difficult to win, less likely to provide a damages award providing an amount that the infringer would have been willing to pay in a hypothetical negotiation, almost impossible to produce injunctive relief even against direct competitors, and easier to overturn on damages and liability. Further, with the AIA, accused infringers usually get to spend 12 to 18 months throwing darts at the claims in suit before a judge even allows the case into court. This has led to large companies – amazingly often the same companies that have spent millions of dollars buying the White House and Congress – simply deciding it is less expensive and much easier simply to infringe patents and fight in court than to deal with technology owner. This model even comes with a fun name: efficient infringement.

So if the land of the free has turned into the land of the free to steal, where are innovators to turn to protect their inventions? Some have turned to Germany, where the courts are efficient experienced, and routinely provide injunctive relief. The problem with Germany is simple: an injunction in Germany prohibits making, using, selling, or importing into … well, Germany. Germany is a nice manufacturing market, especially for high-end automobiles. And the sales market is the largest in Europe. But it is a small fraction of the sales market in the US or China.

Others have gone to to the UK, but the invalidation rates there are well over 50%. Some have gone to Italy and France, but with all due respect to some great food, these are not bastions of technology, particularly in technology manufacturing. Some have even gone to India. But a country that takes seven years to hear a simple complaint about lie-flat airline seats promises no quick relief for complex patent cases. Although some have had recent success in India against Chinese smartphone makers, the reason is likely anti-Chinese sentiment, and is an exception to the sluggishness and unpredictability of Indian courts.

Enter China. The Middle Kingdom. The Wild East. The Great Red Hope. Whatever you want to call it, this communist nation, once the laughing stock of all things IP, has created an effective, efficient, and remarkably fair patent enforcement system. We believe it is the most effective forum worldwide. Why? One word: leverage.

The magic of China: Exports

Why China, then? One factor outweighs the rest combined: the Chinese manufacturing market. As everyone knows, virtually everything we own these days originates in China. From clothes, to food, to toys, it is difficult to find anything that does not come from the Middle Kingdom. But the big item is electronics. Watches, smartphones, gaming systems – virtually anything electronic is made in China. For instance, Qualcomm makes more than half of its revenue from China. The smartphone market there is the biggest in the world.

Because of its huge sales market, China creates significant leverage for patent cases targeting making, using or selling products. But the real magic of China is exports. Unlike most nations that enjoin infringing sales, uses, manufacturing and imports, China also bans exports of infringing products. This means that a winning party can enjoin exports of anything made in China (again, pretty much everything). For example, if Apple were to lose a patent case in China on mobile functionality, then because it makes all of its mobile products in China, it could quickly be prevented from selling products anywhere in the world! In a motion to compel arbitration in the Northern District of California in October 2015 related to a patent case filed in China by one of its Chinese suppliers, BYD, Apple warned of exactly this result (pictured above).

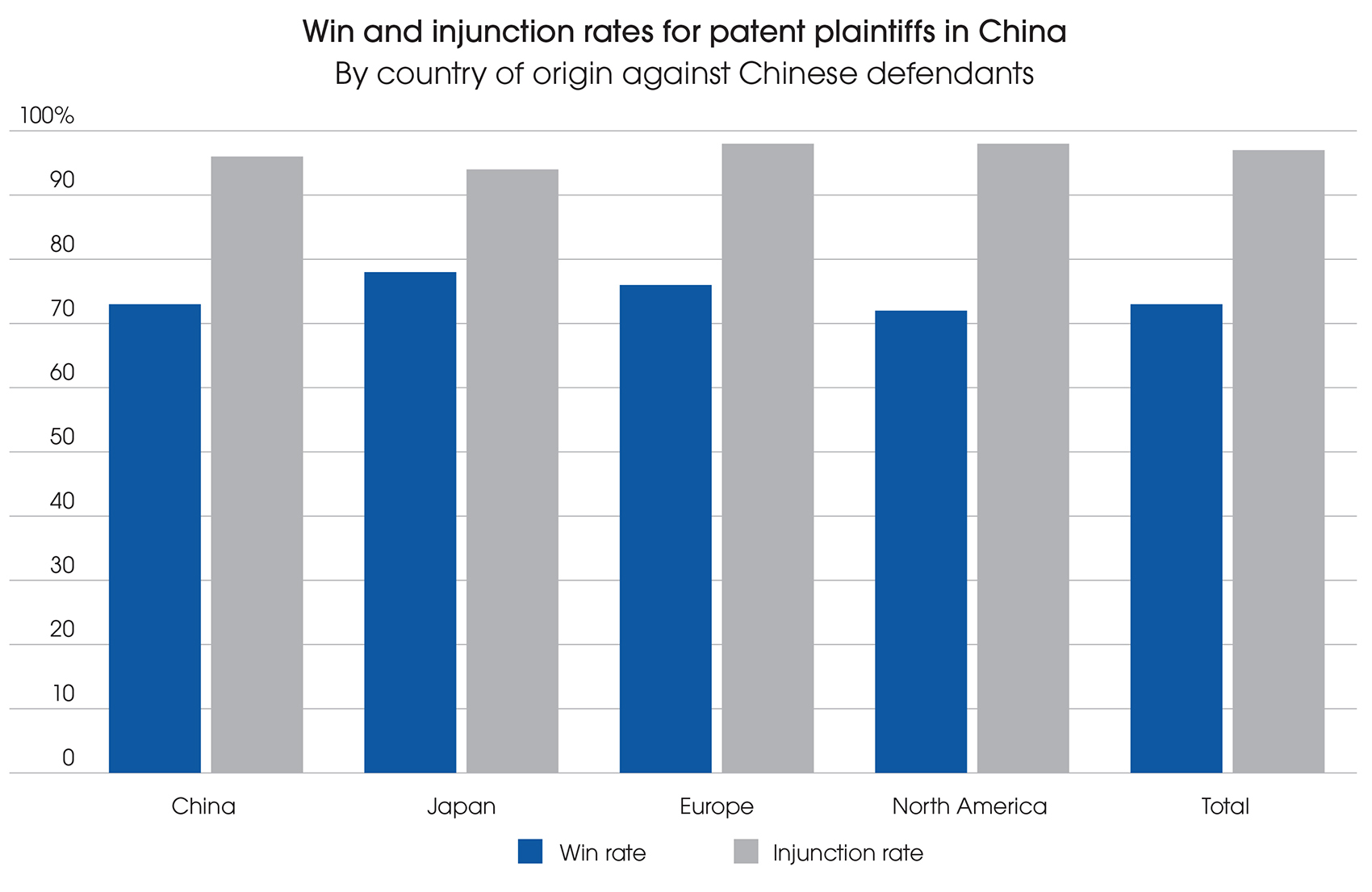

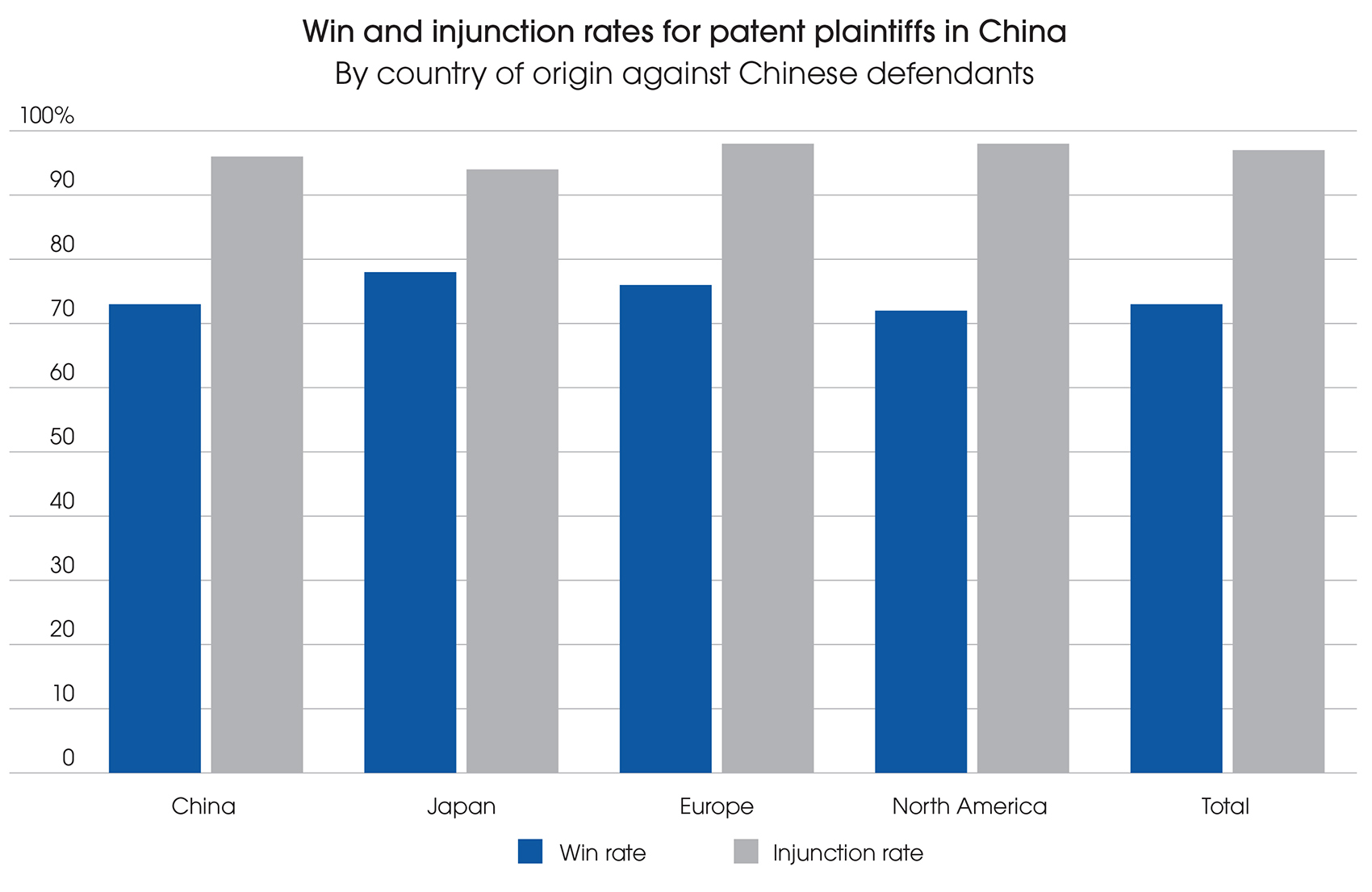

But how often is an injunction actually issued in a Chinese patent case? Virtually always. Across all jurisdictions, the injunction rate for a winning patent litigating is from 98% to 100%. So why have we not heard about this until recently? None of the major tech companies have been enjoined in China – why not? Quite simply, because the system is too new. It was only in November 2014 that China instituted dedicated IP Courts. Changes to the system have come quickly. It is only now that we are seeing more headline filings such as by Qualcomm against Chinese handset maker Meizu and Huawei against Samsung.

High win rates

While the magic of China for patent litigation lies in its huge manufacturing base and willingness to grant injunctions on exports, there is a whole lot more for patent owners to like. First, the win rates average around 80%.

Keep in mind that these win rates are for past cases. Because the quality of cases, patents and representation are getting better at a logarithmic rate, these statistics are even more impressive. Indeed, most patents in China are still of low quality. The average patent case is far from what US patent litigators are used to. Most Chinese lawyers present no or very minimal trial graphics or demonstrative exhibits. The arguments are not as refined. And because the system is so new, most litigators in China, by definition, have little experience litigating complex high tech patent cases. So imagine if the patents become top notch. What if the lawyers approach cases like experienced American patent litigators with graphics and other advocacy tools to make the cases easier for the judge to understand? And how about when the arguments are more concise and persuasive? When this happens, the winning percentage should go through the roof. This is the future of patent litigation in China.

Foreign plaintiffs win more than Chinese plaintiffs

A prime misunderstanding I often hear from those who do not closely follow Chinese law is that foreigners have no chance in China because of nationalistic discrimination. Nothing can be further from the truth. For example, last June, Judge Gang Feng of the Beijing IP Court not only revealed, but touted, the fact that in his court in 2015, foreign plaintiffs went 65-0 in patent cases. Obviously this record is impressive, but even more important is the fact that Judge Feng publicly rolled out the red carpet for foreigners. No public official, including judges, says anything publicly that the national government does not support. Therefore, it is clear that the government of China supports advertising its patent courts to foreign plaintiffs.

In addition to these statistics from Beijing, several other studies have shown that foreign patent owners across China win 80% to 90% of the time. Although statistically foreign patentees do extremely well, such parties must still do their homework. This is especially true if they are attacking a Chinese company. But even against Chinese litigants, foreign parties fare well as long as you have a good case and act fairly.

What does it mean to "act fairly"? To meet the reasonability standard for filing against a Chinese entity, the analogy I draw is to filing in China based on a standard essential patent ("SEP"). Although there are no hard-and-fast rules regarding SEPs such as exist in Germany and elsewhere, a good rule of thumb is that a party must show that the licensing offer is fair, reasonable, and non-discrimatory (FRAND). In most cases, proving FRAND-liness is relatively straightforward. First, the patentee should show that they have attempted to work with the defendant before coming into court.

This does not mean that a SEP owner has to wait forever to sue. They must merely show a defined negotiating timeline. This could mean multiple attempts to engage the defendant on multiple fronts, such as a couple of letters to the general counsel or an email or two to the head of licensing. If the potential licensor rejects the offer or simply does not respond, then the patentee has no choice but to file. It may make sense to cap the process with a correspondence saying that if they do not respond within 24 hours you have no recourse but to file a patent suit. The key is to make sure that a judge seeing the exchange of communications will see you are acting reasonably and not wasting court time without first trying to work it out with the other party.

Other than establishing a timeline of negotiation, a SEP filer (or a foreign patentee looking to sue a Chinese company) should research and cite favourable licensing rates. Ideally, these should be licenses of the patent(s)-in-suit or foreign counterparts. But if that is not possible, the patentee should do what damages experts do all the time in the US and find comparable licences in the same industry. Then they should make sure they have made a finite offer to the defendant and show what is asked of the defendant is within the range of prior licences, given various parameters such as the

Georgia-Pacific factors. Now that the SEP owner have shown that your actions are FRAND, the judge (and the Chinese antitrust agencies) are not likely to be annoyed about your SEP case or your case against a Chinese company. In fact, they may be able to get the judge on your side by showing that the Chinese company is acting unfairly.

Be a friend of China

It is probably a good time to discuss the number one rule of doing any business in China, including filing lawsuits: be a friend to China. Multiple Chinese government officials have said this in many contexts. Being a friend to China simply means being at least a net-neutral player in the long-term plans of China's government, people and economy. Obviously if a party can be a net positive, then all the better.

Note that this does not always mean everything a patentee does will help China in the short run. As long as the long-term effect on China is positive, foreign companies can take actions that have negative short-term effects. For instance, perhaps the best thing that could happen to Chinese innovation is to have a major Chinese company lose to a foreign company in a significant patent case. This would show the world once and for all that China is a fair place to litigate. Although the Chinese enforcement already is fair in most cases, such a win for a foreigner would add an exclamation point.

To pick on Apple again, it provides a useful example of short-run versus long-run benefits to China. Many have concerns as to whether large companies such as Apple could actually be enjoined from exporting products from China. The answer is absolutely yes. But what about all of the people working for Apple directly and for them indirectly via Foxconn and others? Will they not lose their jobs? Yes. For about three weeks. And then they will move across the street or to another part of the same factory and start making similar mobile phones – for Chinese companies. Plus, unlike Apple that has a mixed history with the Chinese government regarding giving back to China, Chinese handset makers such as Xiaomi, Huawei, ZTE, Oppo, Viivo and Meizu reinvest their revenue in China. They have much more long-lasting positive effects than foreign companies such as Apple. So an injunction against Apple (or any foreign player) would serve the Chinese national interest of benefiting Chinese players. There might be some short-term discomfort, but long-term China and its people would benefit. And unlike the US and most of the West, China does not set goals on a monthly or quarterly basis, but rather on a five-year-by-five-year basis. This is one of the chief reasons why China has been successful. They can think longer term. And it is in this longer term that any foreigner must provide value.

Additional factors

In addition to the high win rates, large manufacturing and sales market, and virtually guaranteed injunctions, China offers several other advantages for patent owners. For one, the time to trial is very quick: generally one year or less. Further, invalidation rates at the Patent Reexamination Board of the Chinese Patent Office are low, between 20% and 30% for invention patents. Plus, the litigation of invention patents is rarely stayed pending a validity challenge.

Because US-style discovery is not available and because the time to trial is so short, Chinese patent litigation is much less expensive than US litigation. It is approximately the cost of German cases, which makes sense because much of Chinese patent law is based on German law. Forum shopping is widely available as a patentee can file anywhere the infringing product is sold or made. Finally, although discovery requests are not available, asset and evidence freeze procedures are available and are often effective.

China's patent enforcement system has quickly gone from worst to first, and is still improving. Although the system is new, it is based on the reliable and effective German system, with several common-sense tweaks from the US and the courts' experience thrown in. Like many aspects of today's global economy, China is taking the lead in patent enforcement to protect its investments in innovation. As more innovation originates in the Middle Kingdom, more efficient and effective means are required to protect creativity and investment. China appears fully ready to achieve the next level in its quest to become the world's most important economy.

About the author

Erick Robinson is an expert in Chinese patent law and litigation. He is director of patent litigation for Beijing East IP in Beijing, where he leads patent litigation, licensing and prosecution efforts for Chinese and western entities ranging from SMEs to Fortune 100 companies. An experienced US patent attorney and trial lawyer with a technical background in computer science and physics, as well as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and oil and gas, Robinson is a trusted authority on patent and antitrust law in China, has been selected as one of the Leading 300 IP strategists worldwide by IAM for the past three years and is the author of ChinaPatentBlog.com as well as numerous articles on Chinese patent litigation.